Alex Tang

Articles

- General

- Theology

- Paul

- Karl Barth

- Spiritual Formation

- Christian Education

- Spiritual Direction

- Spirituality

- Worship

- Church

- Parenting

- Medical

- Bioethics

- Books Reviews

- Videos

- Audios

- PhD dissertation

Spiritual writing

- e-Reflections

- Devotions

- The Abba Ah Beng Chronicles

- Bible Lands

- Conversations with my granddaughter

- Conversations with my grandson

- Poems

- Prayers

Nurturing/ Teaching Courses

- Sermons

- Beginning Christian Life Studies

- The Apostles' Creed

- Child Health and Nutrition

- Biomedical Ethics

- Spiritual Direction

- Spiritual Formation

- Spiritual formation communities

- Retreats

Engaging Culture

- Bioethics

- Glocalisation

- Books and Reading

- A Writing Life

- Star Trek

- Science Fiction

- Comics

- Movies

- Gaming

- Photography

- The End is Near

My Notebook

My blogs

- Spiritual Formation on the Run

- Random Musings from a Doctor's Chair

- Random Sermons from a Doctor's Chair

- Random Writings from a Doctor's Chair

- Random Spirituality from a Doctor's Chair

Books Recommendation

---------------------

Medical Students /Paediatric notes

Discernment as the Ontological Act of Knowing: A theological-pyscho-social examination of the act of discernment during spiritual direction

Dr Alex Tang, MD, PhD

Paper presented at Research Symposium

.jpg)

.jpg)

Discernment is a critical component in the process of spiritual direction. Spiritual direction is the process in which a spiritual director aids the spiritual directee to discern which of the multiple choices or numerous pathways is the best for the directee. This discernment is an ontological act of knowing. The directee uses various resources to help in his or her discernment. What will be the context in which will help the seeker to receive discernment. It is the purpose of this paper to present that discernment is an ontological act of convictional knowing. Using Shults and Sandage’s intensification of spiritual transformation as the framework and context, with Loder’s convictional learning model, and Dallas Willard’s dimensions of human nature, discernment will be reframed as an ontological act of knowing in spiritual direction. The context of this paper is in the Judeo-Christian tradition.

INTEGRATED THEORIES ON THE PROCESS OF DISCERNMENT

My stance coincides with that of integrated faith-development theorists. Anthony A. Hoekema (1986) mentions movement from the “perverted image” to the “renewed image” and then to the “perfected image” in his structural model of spiritual restoration. Movement from each of these implies a crisis point or a point of ‘knowing’. While these cannot be considered actual stages, I do not discount stages of faith development completely. However, I am deeply influenced by Calvin’s theology of faith development as a process of becoming who the redeemed person already is (rediscovering), especially in light of Paul’s discussion of his spiritual journey in Romans 7.[1] In the following section, I will focus on three of these integrated theories in the process of becoming:

a. Loder’s “logic of transformation” (1989)

b. Shults and Sandage’s intensification model (2006)

c. Willard’s “renovation of the heart” (2002)

Each of these theories will be examined in some detail because I intend to integrate them into a single theory to describe the process of discernment in spiritual direction. I will investigate whether these theories have the elements of person-in-formation, persons-in-community formation, and persons-in-mission formation involved in the process of becoming which forms the foundations of spiritual formation and direction.

a. Loder’s “logic of transformation”

Reformed theologian, psychologist, and educator James E. Loder (1989) offers an explanation that contributes to the understanding of the process of faith formation. Loder’s interest is in explaining how the Holy Spirit brings about transformation in a person. Broadly, a change may be considered first-order if it involves coping mechanisms to reduce anxiety. Primarily behavioural, this transformation is confined to the context in which the person finds himself or herself. Thus, first-order change may be considered an early phase of faith formation or “functional transformation” (Shults and Sandage 2006, 20). In a Christian context, a person may find that he or she fits into a faith community by adopting his or her behavioural practices to experience a sense of belonging. First-order change is not lasting, however, without second-order change.

Second-order change or “systemic transformation”[2] is more complex and involves the development of a new way of knowing and relating to a person’s perception of reality. It entails profound changes in self-identity and understanding the “meaning of life.” In religious terms, it means a new revelation of the sacred akin to “convictional knowing” and is considered a transformation of the human spirit (Loder 1989, 93–122), which is solely the work of the Holy Spirit (1 Cor. 10–16). “Convictional knowing,” writes Loder, “is the patterned process by which the Holy Spirit transforms all transformations of the human spirit” (1989, 93). The act of transformation may be instantaneous or it may take place gradually over a few years. Paul’s autobiographical account of his spiritual journey in Romans 7 is helpful in defining formation and transformation. Formative acts involve a person’s continued and active participation in the process of faith development. Transformation, on the other hand, involves discontinuity as the Holy Spirit intervenes. Paul’s description of his tour in heaven (2 Cor. 12:2) thus may be interpreted as a transformation. In my opinion, Loder’s “convictional knowing” is the point when discernment occurs in spiritual direction. Spiritual formation forms the matrix for this to occur.

The key to faith formation and transformation of the human spirit is both the work of the Holy Spirit and the willingness of a person to yield to such guidance. However, formative acts may not lead to transformation. They provide only the fertile soil in which transformation may occur. Many writers, as already mentioned, use the metaphor of seeds and germination to describe formative acts. In contrast, the dynamic process of transformation is often prompted by a period of conflict. Loder presents his “logic of transformation” by building on the foundation of his “four dimensions of [human] being” (1989, 67–91).

According to Loder, four dimensions make up a person’s being: self, world, void, and the Holy. The “lived world” denotes people’s experiential construct of reality, which is the foundation on which they form relationships. The “void” is the source of people’s fears because it represents a negation of their world. Whenever the void encroaches on a person’s lived world, it creates conflict and anxiety. The self will then try to restore a balance because it is unable to live with conflicts and anxiety. “The Holy” offers the self a sense of transcendence, which is an antidote to the void.[3] The way the self deals with the conflict caused by the void is a process that Loder calls the “logic of transformation,” which is a series of steps to resolve the conflict (1989, 35–44).[4] The resolution of conflict requires the assistance of the Holy to create a new balance and world. This new balance and world is what Loder associates with “convictional knowing” because it entails a new way of looking at things.

Another way of understanding Loder’s “convictional knowing” is as worldview.[5] Brian J. Walsh and J. Richard Middleton define a worldview as “a model of the world which guides its adherents in the world. It stipulates how the world ought to be, and it thus advises how its adherents ought to conduct themselves in the world” (1984, 32). It is, in other words, an ontological perception. Christian author and philosopher James W. Sire initially defined a worldview as “a set of presuppositions (assumptions which may be true, partially true, or entirely false) which we hold (consciously or subconsciously, consistently or inconsistently) about the basic make-up of our world” (1976, 19). This is largely an epistemological description. Twenty-eight years later, he offered a more refined definition:

A worldview is a commitment, a fundamental orientation of the heart, that can be expressed as a story or in a set of presuppositions (assumptions which may be true, partially true, or entirely false) which we hold (consciously or subconsciously, consistently or inconsistently) about the basic constitution of reality, and that provides the foundation on which we live and move and have our being. (2004, 122)

This expanded definition combines ontological, epistemological, and ethical implications. It still has a cognitive component (presuppositions) but allows for other ways of knowing (learning by storytelling). In addition, it allows for a transformed way of thinking and living. In other words, Sire’s (1976) more comprehensive definition implies not just head knowing but also heart knowing as it operates in everyday life, which aligns closely with convictional knowing. Christian faith formation and transformation are the processes by which people align their worldviews with Christ’s teachings.

Loder (1989) conceives of the logic of transformation as a cognitive event because it is the process whereby the self comes to discover a new way of knowing. The logic of transformation occurs in a series of steps involving both continuity and discontinuity: (1) conflict, (2) interlude for scanning, (3) constructive act of imagination, (4) release and opening, and (5) interpretation.

Conflict occurs whenever discontinuity arises in a person’s lived world. It may result from an accident, an illness, the loss of a loved one, or a sense of restlessness that threatens the continuity or stability of our lived world and provokes painful anxiety. Because the self cannot live with this anxiety, it begins scanning for possible ways to resolve the conflict and reduce the anxiety. This period of scanning may last moments or years until suddenly a solution appears. The solution may not be due to logical reasoning but is a constructive act of imagination. I propose that this ‘constructive act of imagination’ is what discernment is. It lead to ‘convictional knowing’. Two or more non-compatible solutions may come together to produce a workable resolution to the conflict. Loder describes this key event of transformation as “insight felt with intuitive force” (1989, 3). The appearance of the solution—sometimes known as the “aha” moment—is then accompanied by a release of energy, which is the response of the unconscious and reduces the anxiety level. Simultaneously, an expanded knowing or consciousness occurs, resulting in a new lived world in which people are able to see things more clearly than before. The final stage is interpretation, which occurs when people use their transformed knowing to reconstruct or improve upon their lived world. This reworking may be oriented both forward and backward in time. In the reworking of people’s lives forward, which Loder calls correspondence, they now have a renewed sense of identity and purpose. In reworking backward, which the theorist terms congruence, people are able to understand past experiences in a new light because of their expanded understanding. Correspondence and congruence is the result of ‘convictional knowing’.

This process may describe the way how discernment works. The logic of transformation is facilitated by the Holy in the person of the Holy Spirit. Convictional knowing may lead to a deeper experience of self and greater insight into God, which, in turn, changes the outlook and lifestyle of the knower.

b. Shults and Sandage’s intensification model

Theologian F. LeRon Shults and psychologist Steven J. Sandage, in their intensification model of spiritual transformation (2006), build on Loder’s work to clarify the Christian faith journey of formation and transformation. They correlate the Christian faith formation tradition of purgation, illumination, and union with Loder’s five steps of the logic of transformation as follows:

The dynamics of purgation seem naturally correlated to experiences that Loder described in terms of the conflict and tension that lead to scanning. The dynamics of illumination are more easily connected to what Loder called imaginative insight, the construction of a new way of understanding one’s self as spirit in relation to one’s neighbors and God. Finally, the unitive dynamics of the classical third way can be described in terms of the release and opening of the human spirit into a new sense of relational unity and intimacy. (29)

Further, Shults and Sandage (2006) suggest that the dynamics of intensity, intentionality, and intimacy in relationships shape a person’s faith formation (29). Loder’s (1989) “logic of transformation” deals largely with a person as the knower. Shults and Sandage bring into the equation relationality. They recognise that relationship is a foundational concept in faith communities and argue that relational intensity is essential for human well-being. Intentional relation to others and the need for relational intimacy are essential for the development of personhood. Spiritual transformation occurs when the dynamic of these relationships leads to “redemptive intimacy,” which is a deepening relation with God (89). Shults and Sandage define spiritual transformation as “a process of profound, qualitative change in the self in relationship to the sacred” (163). While Loder’s theory is similar to the formative strand of person-in-formation, Shults and Sandage cover the formative strands of persons-in-community formation. It may be noted that Shults and Sandage moved the understanding of faith formation from the purely cognitive (transformational logic) to involve the relational or communal aspects.

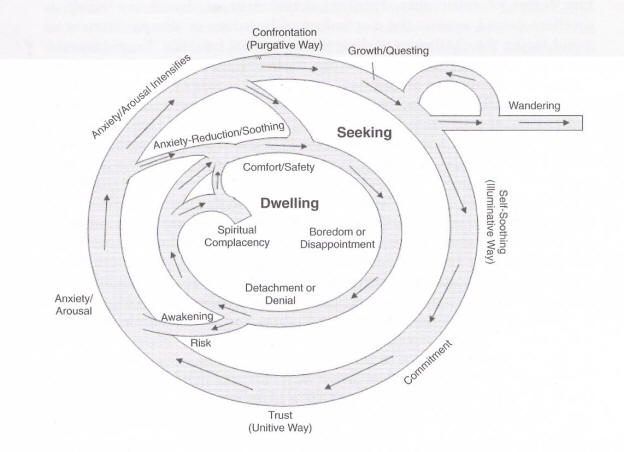

Shults and Sandage (2006) suggest that faith formation does not occur independent of other spiritual knowers or seekers. It involves communities and spiritual journeys. The dynamics of their theory correlate with the findings of American sociologist Robert Wuthnow (1998), who discovered a continual movement between “dwelling” and seeking in people’s spiritual journeys.[6] Spiritual “dwelling” is a place of comfort that offers a balance between the void and the Holy. A conflict between these dimensions is often what thrusts some people into a spiritual seeking or quests. Such seeking continues until a resolution that involves a transformation is achieved. When such resolution is not achieved, people continue to wander in their seeking. Figure 1 illustrates the relation between spiritual “dwelling” and seeking in the Shults and Sandage model[7].

In this intensification model, the inner ring represents the “cycle” of spiritual “dwelling”. It includes “connection to a spiritual community and tradition that legitimizes certain rituals and spiritual practices and provides a sense of continuity to spiritual experience” (Shults and Sandage 2006, 32). Staying in the cycle of spiritual “dwelling”, however, may lead to boredom and spiritual stagnation. This stagnation, in turn, may prompt some persons to move toward the outer cycle of spiritual seeking, which involves “systemic and redemptive transformation.” When transformed, such people may re-enter the cycle of spiritual “dwelling” with a renewed sense of purpose and a deeper relationship with God.

Figure 1. Balancing spiritual dwelling and seeking. Source: Adapted from Shults and Sandage 2006, 33.

Shults and Sandage’s (2006) model seems to emphasise the outer ring of spiritual seeking more than the inner ring of spiritual “dwelling”. While fundamentally agreeing with their model, I would suggest that, in addition to boredom and spiritual stagnation, crises in life may drive some to move into the cycle of spiritual seeking. As shown in Loder’s (1989) dimensions of being, any discontinuity in a person’s lived world will create the impetus to seek a resolution.

Faith development is not static but dynamic. Shults and Sandage’s (2006) description of the spiritual life allows for times of movement and times of rest. In this way, faith development is like biological growth: It occurs in spurts, not continuously. Their theory involves communities as the site of spiritual “dwelling” and seeking. They refer to such communities as “containers” in which spiritual formation and transformation take place and use the metaphor of a crucible of spiritual transformation. The crucible is defined as a “container or melting pot for holding intense heat and pressure that can transform raw materials and catalytic agents into qualitatively different substances” (31). Alternative metaphors include “holding environments” or “cultures of embeddedness.” (172). Sandage writing in his section of the collaborative book (2006) elaborates that “[t]hese systemic cultures of embeddedness can provide a supportive relational context out of which spiritual formation and transformation can emerge. This holding and shaping function has been likened to developmental scaffolding” (172). The intensification model of transformation involves faith-formative processes as well as a container within which these processes interact.

To Loder’s (1989) “convictional knowing” through the “logic of transformation,” Shults and Sandage (2006) add the role of community as a crucible for spiritual “dwelling” and seeking. Community is the context for the Loder’s logic of transformation. They also add a sense of dynamism and movement to faith formation. However, these two theories both portray knowers who are very cognitively oriented. There is much knowledge but no passion. The key emotion that drives transformation seems to be anxiety. Where, then, is the motivational passion that drives faith formation?

Shults and Sandage (2006) emphasise relational intentionality that leads to redemptive intimacy. They underscore the role for volitional intention in faith formation. A person has to want to grow or develop spiritually. The next theory deals with the heart of the process. However, not all people want to relieve their conflicts or anxiety by entering into Loder’s (1989) transformational logic or the intensification model of spiritual transformation. Instead, they deal with their anxiety or conflict by distracting themselves with entertainment, alcohol, drugs, or others forms of distractions.

c. Willard’s “renovation of the heart”

Dallas Willard underscores the importance of personal volition, intent, or intentionality in faith formation when he begins Renovation of the Heart with the declaration that “we live from our heart” (2002, 13). By heart, he means “the executive center of a human life. The heart is where decisions and choices are made for the whole person” (30). Discernment occurs when the participant wants to be the knower i.e. the involvement of intentionality and volition.

Willard (2002) postulates six “dimensions” that make up human nature:

1. Thought (images, concepts, judgments, inferences),

2. Feeling (sensation, emotion),

3. Choice (will, decision, character),

4. Body (action, interaction with the physical world),

5. Social context (personal and structural relations to others),

6. Soul (the factor that integrates all of the above to form one’s life). (30)

In Willard’s model of human nature, the mind consists of thought and feeling. The will is synonymous with his definition of heart and spirit. The soul is that which functions to integrate the other five dimensions.

Willard (2002) defines spiritual formation as the “Spirit-driven process of forming the inner world of the human self in such a way that it becomes like the inner being of Christ himself” (22). He elaborates:

Spiritual transformation only happens as each essential dimension of the human being is transformed to Christ-likeness under the direction of a regenerate will interacting with constant overtures of grace from God. Such transformation is not the result of mere human effort and cannot be accomplished by putting pressure on the will (heart, spirit) alone. (41–42)

Willard (2002) proposes that spiritual formation is character formation as a result of personal choice interacting with grace from God (19). However, as a philosopher, he notes that “psychological and theological understanding of the spiritual life must go hand in hand” (74). He coins the acronym VIM to describe his model of spiritual formation. VIM stands for Vision of living in the Kingdom of God now, Intention to be a “Kingdom person,” and Means of spiritual transformation (85–90). The latter pertain to “replacing the inner character of the ‘lost’ with the inner character of Jesus: his vision, understanding, feelings, decisions, and character” (89). Doing so is achieved by identifying and modifying the six aspects of human personality (nature)—thought, feeling, choice, body, social context, and soul—that prevent us from becoming like Jesus. Once these failings have been identified, a person can take steps to reorient his or her inner self to a new worldview and cultivate new habits, attitudes, and feelings. Willard’s approach involves volitional intentionality on the part of individuals to take the necessary steps.

The chief means of spiritual formation suggested by Willard (2002) is the study of the Scriptures and practice of the spiritual disciplines. His model of faith communities aligns living in the kingdom of God with intentional efforts to emulate Jesus Christ. Agreeing with Willard, Evan B. Howard relates the VIM model to his own insights on faith communities:

Christian spiritual formation involves a reorientation and rehabituation of our lives. It aims at full harmony with Christ. It is divine insofar as it responds to divine grace; it is human insofar as it is intentional and ongoing. It is expressed in life. (2008b, 270)

Both Willard and Howard have identified the salient aspects of spiritual formation: reorientation and harmony with Christ, human intentionality, divine grace, and ongoing process.

However, Richard V. Peace points out that Willard’s model, in its emphasis on personal introspection, may produce very individualistic Christians (2004, 164). Holistic spiritual formation is personal but not individualistic. Willard does devote Chapter 13 in his book to the idea of community. He reveals “God’s plan for spiritual formation in the local congregation,” suggesting that it consists of (1) making disciples for Jesus Christ, (2) engaging these disciples in the Trinitarian relationship, and (3) inner transformation so that disciples follow “the words and deeds of Christ” (2002, 240–51). Jeff Sickles similarly concurs with Peace that Willard’s model tends to focus on developing individualistic Christians (2004, 180–81).[8]

Willard has contributed much to the study of spiritual formation. However, I agree with Peace (2004) and Sickles (2004) that Willard’s (2002) approach to faith communities is individualistic. His approach places considerable emphasis on a person’s volition or decision-making. The role of the Holy Spirit is acknowledged, but the precise nature of spiritual transformation is not explored in depth. Moreover, his division of human nature into mind, body, soul, and spirit is artificial. The process of spiritual formation involving these dimensions may not be as simple and orderly as he conceives it to be.

The heart as the “executive centre” is Willard’s (2002) thesis for his faith formation. His focus is on cognitive understanding and disciplined development of Godly habits. Willard does not seem to take into account the affective role of the heart. Emotions are perceived as something to be controlled rather than something to be experienced and redirected. I suggest that faith communities also involves identifying, accepting, and redirecting a person’s emotions. Passions, when under rational cognitive control may be a powerful motivator in faith communities.

Biblical writers refer to the human heart as the centre not only of commitment and conscience but also of the emotions. It is the source of strength for physical activities. Old Testament scholar Bruce K. Waltke explains that, in the Bible, the word heart denotes “a person’s centre for both physical and emotional-intellectual-moral activities” (1996, 331). According to Kittel, Friedrich, and Bromiley, the New Testament displays a “rich usage of kardía (heart) for a. the seat of feelings, desires, and passions; b. the seat of thought and understanding; c. the seat of the will; and d. the religious centre to which God turns, which is the root of religious life, and which determines moral conduct” (1985, 416). Commenting on Matthew 22:37, “Love the Lord your God with all your heart,” Waltke observes that “love here is more than emotion[;] it is a conscious commitment to the Lord” (1996, 332). This approach suggests that the heart is both the executive and emotive centre of a human being, which I refer to as the biblical heart.

The role of the biblical heart as emotive centre in faith formation has been considered in the literature. Affections are important in faith formation. The heart controls the mind, not the other way around, as psychologist and philosopher William James, a pioneer in the study of the phenomenon of religious experience, points out in his seminal essay “The Will to Believe” ([1897] 1956, 1–31). The true motivators for faith formation come from the biblical heart. These motivators are (1) a deep sense of sin and (2) an insatiable hunger for God. This idea links back to the intrinsic human yearning to restore the fallen imago Dei. In Loder’s (1989) model, human yearning is the self’s attraction to the Holy. It is often not an intellectual understanding of theological doctrines but a passionate heart for God that leads to spiritual growth. An appropriate paradigm of spiritual formation will include passion or the biblical heart as a motivator via the work of the Holy Spirit.

The biblical heart is susceptible to influences that affect spiritual formation. These influences may be sociopolitical, such as religious pluralism, political and personal freedom in the community, or socioeconomic status and relationships. They may also be psychocultural, such as heritage, personal health, life events, lived experiences, level of education, and underlying philosophy of life. Hence, the Bible warns to guard the biblical heart (Prov. 4:23).

Summary

In the spiritual process of “becoming,” Loder (1989) contributes to the understanding of formation and transformation in an individual, and Shults and Sandage (2006) contribute to the idea of dynamic movement in the spiritual journey and its tie with the person’s faith community. Discernment is the convictional act of knowing which happens when there is a leap of faith during the process of scanning, seeking, and searching when seemingly unrelated and even paradoxically events come together to reveal an elegant solution in a spiritual direction situation. We call this event discernment. Discernment is an ontological act of knowing because it affects the past, present, and future worldview of the recipient. In Williard’s approach, knowing comes before action. Volition leads to formation and transformation of the individual.

.jpg)

Further reading

Loder, James E. 1989. The transforming moment. 2nd ed. Colorado Springs, CO: Helmers and Howard.

———. 1998. The logic of the spirit: Human development in theological perspective. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Shults, F. LeRon, and Steven J. Sandage. 2006. Transforming spirituality: Integrating theology and psychology. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic.

.jpg)

Questions for Discussion

1. What is the psycho-social nature of discernment in spiritual direction?

2. Will this definition and understanding of the process of discernment be applicable across borders and cultures?

3. What are the tools or techniques that will be useful to help our directee achieve the ‘constructive act of imagination’?

4. Will there be place for intervention from Higher Power or is the process purely a psycho-social one?

[1]. It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss who the “wretched man” is in Romans 7:24. My personal inclination is that Paul is referring to himself and that Romans 7 gives us a glimpse into his spiritual journey.

[2]. Shults and Sandage, using the framework of systems theory, describe systemic transformation as dealing with the “healing or reordering of the broader relations within whom a person’s spirituality is embedded. . . . [F]ocus is on the health and wholeness of the human spirit in all its relational contexts” (2006, 20).

[3]. The Christ event, according to Loder, is a “double negation.” The death of Christ on the cross is a negation. At the crucifixion Christ became sin, thereby causing all sins to be cancelled. The resurrection is another negation, cancelling all so that new beings in Christ may come to be. This double negation is the central thesis making Loder’s “logic of transformation” possible (1989, 159–161, 223).

[4]. Loder expanded on this concept in his later book The Logic of the Spirit: Human Development in Theological Perspective (1998).

[5]. There are Christian worldviews but not “the” Christian worldview. While remaining within the biblical framework, a Christian worldview may change in response to culture, politics, or social influences.

[6]. Although Wuthnow’s 1998 study is not specifically focused on the Christian faith and is based on data from North America, his conclusions are recognised as universally applicable.

[7]. Shults and Sandage credit educators Barbara and Don Fairfield of Lanham, MD, with developing the original diagram. Sandage first adapted it for his crucible theory of transformation in couples’ relationships and then, together with Shults, for their intensification model of spiritual transformation (Shults and Sandage 2006, 33).

[8]. Individualistic Christians are more concerned with their own inner spiritual lives than with the world at large. They are inward-looking in their spirituality and perceive their CFC as a supplier of spiritual goods rather than as a community they are a contributing part of.