Alex Tang

Articles

- General

- Theology

- Paul

- Karl Barth

- Spiritual Formation

- Christian Education

- Spiritual Direction

- Spirituality

- Worship

- Church

- Parenting

- Medical

- Bioethics

- Books Reviews

- Videos

- Audios

- PhD dissertation

Spiritual writing

- e-Reflections

- Devotions

- The Abba Ah Beng Chronicles

- Bible Lands

- Conversations with my granddaughter

- Conversations with my grandson

- Poems

- Prayers

Nurturing/ Teaching Courses

- Sermons

- Beginning Christian Life Studies

- The Apostles' Creed

- Child Health and Nutrition

- Biomedical Ethics

- Spiritual Direction

- Spiritual Formation

- Spiritual formation communities

- Retreats

Engaging Culture

- Bioethics

- Glocalisation

- Books and Reading

- A Writing Life

- Star Trek

- Science Fiction

- Comics

- Movies

- Gaming

- Photography

- The End is Near

My Notebook

My blogs

- Spiritual Formation on the Run

- Random Musings from a Doctor's Chair

- Random Sermons from a Doctor's Chair

- Random Writings from a Doctor's Chair

- Random Spirituality from a Doctor's Chair

Books Recommendation

---------------------

Medical Students /Paediatric notes

The Nature of Spiritual Formation

Dr Alex Tang, 15 Feb 2010

Writing to the Christians in Corinth about spiritual transformation (2 Corinthians 3:18), Paul notes that “we, who with unveiled faces all reflect the Lord’s glory, are being transformed into his likeness with ever-increasing glory, which comes from the Lord, who is the Spirit.” It is Paul’s intention to emphasize (1) that in spiritual transformation Christians (individuals and the Christian faith community) will be transformed into a likeness of Christ, (2) that this transformation is an ongoing process, (3) that it is Trinitarian, (4) that the Holy Spirit is involved in this transformation, and (5) that God’s glory is thereby restored. Theologian Darrell L. Bock in New Testament Community and Spiritual Formation comments that 2 Corinthians 3:18 is the verse in the New Testament that best describes the concept of spiritual formation (2008, 105).

Commenting on this biblical verse, theologian R. P. Martin adds:

At all events, the discussion reaches its peak with Paul’s asseveration that believers in Christ live in a new age where “glory” is seen in the Father’s Son and shared among those who participate in that eon. It is the Spirit’s work to effect this change, transforming believers into the likeness of him who is the ground plan of the new humanity, the new Adam, until they attain their promised destiny as “made like to his Son” (Rom. 8:29) and enjoy the full freedom that is their birthright under the terms of the new covenant. (2002, 70)

Christ is thus the embodiment of God’s revelation and glory, through whom is offered a new order of salvation, reconciliation, and righteousness. Christians are transformed gradually (from glory to glory) until they become like Jesus, who is the image of God’s glory. The agent of this transformation is the Holy Spirit. What is described here is the biblical and theological nature of Christian spiritual formation. These foundations of Christian spiritual formation will be examined in the following sections:

1. Sanctification and spiritual formation

2. The telos of Christian spiritual formation and its formative strands

SANCTIFICATION AND SPIRITUAL FORMATION

My approach is from a Presbyterian/Reformed perspective; however, I will also draw from the insights of other denominations and traditions when necessary. John Calvin was able to appreciate theologically the interplay of balancing justification (regeneration) and sanctification. In 1535, he published his Institutes of the Christian Religion, a treatise that K. S. Latourette calls “the most influential single book of the Protestant Reformation” (1975, 752). The Westminster Larger Catechism, which, in part, is based on the Institutes, asks in question 77, “Wherein do justification and sanctification differ?” The answer is as follows:

Although sanctification be inseparably joined with justification, yet they differ, in that God in justification imputes the righteousness of Christ; in sanctification his Spirit infuses grace, and enables to the exercise thereof; in the former, sin is pardoned; in the other, it is subdued: the one does equally free all believers from the revenging wrath of God, and that perfectly in this life, that they never fall into condemnation; the other is neither equal in all, nor in this life perfect in any, but growing up to perfection (Vos 2002, 173).

Justification occurs when sin is pardoned because of Christ’s righteousness, and it is a one-time event. Sanctification occurs when the Holy Spirit infuses grace for the control of sin, and it is an ongoing process leading to perfection in this life. Expanding on this distinction, Reformed theologian Anthony A. Hoekema explains that sanctification is that “gracious operation of the Holy Spirit, involving our responsible participation, by which he delivers us from the pollution of sin, renews our entire nature according to the image of God, and enables us to live lives that are pleasing to him” (1989, 192).

Sanctification takes place immediately after justification, also known as regeneration in a new believer’s spiritual life (Packer 1985, 925). Comparing justification or regeneration with sanctification, systematic theologian Robert P. Lightner notes that the former is (1) purely a work by God, whereas sanctification needs the new believer’s cooperation; (2) instantaneous, whereas sanctification is a process; and (3) a gift from God, whereas sanctification “results in part from obedience and faithfulness to Him” (1994, 42–43). Sanctification is a process that depends on a person’s willingness to obey and be faithful to God. As noted above, sanctification is also “infused grace” by the Holy Spirit while one is “growing up to perfection.”

Calvin was very aware of the tension between justification and sanctification, as well as of the danger of emphasizing only one or the other, and sought to keep the balance. Unfortunately, after Calvin, sanctification was given precedence over justification by Reformed churches. The scope of sanctification or “growing up to perfection” was narrowed to the teaching of Scripture and living a disciplined life. Cognitive knowledge of Scripture and appropriate behaviour became the ethos of the Reformed/Presbyterian tradition. These developments, unfortunately, led to a “sanctification gap,” which, in turn, led to legalism, self-righteousness, and obscurantism[1] (Leith 1981, 80).

What, then, is the scope of sanctification? Is it limited to individuals, or is it related to the world in which they live? Theologian Bradford A. Mullen (1996) suggests two aspects of sanctification: (1) sanctification according to God’s creative design and (2) sanctification according to God’s redemptive purposes.

In sanctification according to God’s creative design, Mullen notes that “God created the universe and human beings perfect (i.e., sanctified)” (1996, 709). This “perfect” or what I term shalom creation was distorted when Adam and Eve sinned. The biblical narrative climaxes with God making holy or perfect His fallen creation. Intrinsic to this perspective is that sanctification applies to God’s entire creation. Theologian Douglas Moo concurs when he states in his commentary on Romans 8:19–25 that “both creation and Christians (1) suffer at present from a sense of incompleteness and even frustration; and (2) eagerly yearn for a culminating transformation” (1996, 513). God’s creation is no longer perfect because it has become a fallen creation.

Sanctification, according to God’s redemptive purpose, relates to his actions in redeeming a fallen creation. This redemptive purpose involves sending his Son to die on the cross, thus enabling humans to receive forgiveness and redemption. It involved God’s calling out a specific group of people to be his instruments in redeeming the created order. God’s redemptive purpose includes using his people to establish the kingdom of God on earth. Therefore, sanctification has a wider scope than that of “justifying” an individual person. It is interconnected with God’s redemption plan to make his entire creation holy. Sanctification includes not only God’s redemption of his people but also a missional outreach to non-believers and care of creation.

Not all theologians agree with this construct. Millard J. Erickson, for example, narrows his scope of sanctification to apply to individual believers only. According to him, “[S]anctification is the continuing work of God in the life of the believer, making him or her actually holy. By ‘holy’ here is meant ‘bearing the likeness of God’” (1999, 980). Jesus is the perfect image of God (2 Cor. 4:4), so it may be inferred that sanctification is a process of becoming like Christ. However, by narrowing the scope of sanctification without a connection to the Christian faith community and to the created order,[2] Erickson runs the risk of sanctification’s becoming a purely individualistic spirituality.

I understand sanctification to be synonymous with Christian spiritual formation. The working definition of Christian spiritual formation is the intentional and ongoing process of inner transformation to become like Jesus Christ himself, to become with others a communal people of God, and to become an agent for God’s redemptive purposes. It is growing into holiness or perfection. While I recognise that there are different interpretations of perfection and sanctification, such as John Wesley’s concept of “entire sanctification,” I will focus on the Reformed theological interpretation of progressive sanctification.

There are others who consider Christian spiritual formation a means of sanctification. Willard[3] describes the relationship of sanctification and spiritual formation as follows:

Sanctification is not an experience, though experiences of various kinds may be involved in it. It is not a status, though a status is maintained by means of it. It is not an outward form and has no essential connection with outward forms. It does, on the other hand, become a “track record” and a system of habits. It [sanctification] comes about through the process of spiritual formation, through which the heart (spirit, will) of the individual and the whole inner life take on the character of Jesus’ inner life. (2002, 226; italics mine)

In this perspective, sanctification is achieved through Christian spiritual formation, whereby people are transformed into the character of Christ. When considered as a process, sanctification and Christian spiritual formation are essentially the same with the similar formative elements and desired outcomes. On this point, I differ with Willard because I consider sanctification and Christian spiritual formation to be essentially the same. Sanctification is not a “system of habits” but a transformation of a person to holiness. It is not behavioural modification but developing a Christ-like holy character. Sanctification and Christian spiritual formation are two nuanced terms describing the same process. Sanctification is a description from the theological perspective while Christian spiritual formation is a description from the “growing into holiness” perspective. Hence, Christian spiritual formation is not a means to sanctification but is sanctification.

In summary, sanctification is that work of the Holy Spirit with the willing participation of believers to restore the fallen image of God and develop habits of living that are pleasing to God. The scope of sanctification includes not only personal salvation but also God’s redemptive purposes for his creation. Sanctification and Christian spiritual formation are the same. The next section will examine the goals of Christian spiritual formation and its formative strands.

THE TELOS OF CHRISTIAN SPIRITUAL FORMATION AND ITS FORMATIVE STRANDS

Christian spiritual formation fulfils God’s creative design and redemptive purposes. Therefore, the goals of Christian spiritual formation are as follows:

- Individual believers’ acquiring a Christ-like character,

- Development of a people of God,

- Establishment of the kingdom of God and the healing of the whole of creation.

Intrinsic to Christian spiritual formation, therefore, are three formative strands that will achieve the desired goals:

- Person-in-formation,

- Persons-in-community formation,

- Persons-in-mission formation.

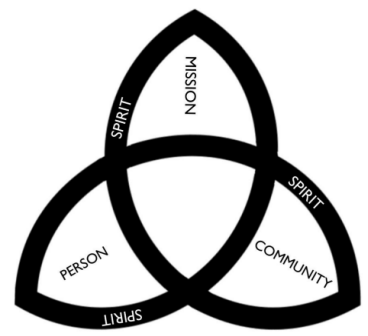

It may be noted that these strands are components of one process and not separate processes. Often, their functions overlap and are indistinguishable from one another as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Formative strands of spiritual formation. Source: Reed (2010, 160)[4]

Figure 1 is one way to visualise the inter-relatedness of these three formative strands. The three points of the person, community, and mission are connected and inseparable from one another. The three strands do not function alone. They are joined by the presence and activity of the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit is the active agent attending to person-in-formation, persons-in-community formation, and persons-in-mission formation. Believers are invited to journey with the Holy Spirit along all these three points. The goals of Christian spiritual formation and its formative strands will be addressed as follows:

a. Person-in-formation to Christ-likeness,

b. Persons-in-community formation to become a people of God,

c. Persons-in-mission formation in the kingdom of God and the healing of creation.

a. Person-in-formation to Christ-likeness

Person-in-formation is the process whereby individuals develop their characters so that they become like Christ (Gal. 4:19; Rom. 8:29; 2 Cor. 3:18), thus restoring the imago Dei. Christ is the perfect image of God. Therefore, becoming more like Christ means becoming more like God. It does not mean that one becomes God. It does mean, however, that one achieves the holiness of perfection. Jesus urges his disciples, “Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect” (Matt. 5:48). Paul declares that the desired outcome of his ministry is to “present everyone perfect in Christ” (Col. 1:28).

One of the metaphors Paul uses to describe this process involves “taking off your old self with its practices” and “putting on the new self, which is being renewed in knowledge in the image of its Creator” (Col. 3:9–10). The metaphor refers to taking off a soiled shirt and putting on a clean one. This is an apt metaphor because person-in-formation is the process of developing a new Christ-like character by removing the bad habits and attachments of the old self. Others have described this process as a pilgrimage or journey. Both of the latter metaphors are helpful because they emphasize change and movement. There are differences, however, between them. A pilgrimage is made with a number of stops along the way, often holy or sacred places the pilgrim wants to visit. A journey has a fixed destination, but the route may vary depending on unforeseen contingencies. Some scholars liken the person-in-formation pilgrimage to a faith-stage process of development, suggesting that spiritual growth in individuals follows a certain number of predictable stages. Often, the person has to complete one stage before going on to the next stage. Later, I will critique this thinking.

I prefer the journey metaphor because it recognises that an individual develops at his or her own pace. Christian educator Suzanne Johnson expresses the point this way:

Rather than a matter of predictable, irreversible stages, formation of character is like an unfolding drama, with unpredictable twists and turns in the plot. There are fits and starts, sudden shifts and surprises, as well as imperceptible growth. Christian character is shaped as believers learn, through the guidance of the faith community, to orient their entire existence to God’s redeeming work in Jesus Christ. . . . A key thesis is that spiritual formation is not a thing apart from but rather the core dynamic in becoming Christian. (1989 104)

Person-in-formation may be described as the ongoing process of a redeemed person’s interacting with the complexities of life while accepting the help of the Holy Spirit and other Christians in trying to conform his or her character to that of Jesus Christ. It is not a matter of doing the right things (right practices) but of becoming the right person (like Christ). This idea will be expanded later when the process of spiritual formation is examined in light of theology, psychology, and the social sciences.

The early Church taught that the process of a person’s spiritual growth involves purgation and illumination, culminating in oneness with God or theosis. In this regard, historian and theologian Timothy George makes an interesting observation in For All the Saints: Evangelical Theology and Christian Spirituality:

But evangelical piety turns upside down the medieval paradigm of a pathway to God. There the journey of faith began with purgation, moved on to illumination, and finally ended in unification, that is, union with God. In the evangelical understanding, we began with union with Christ (the new birth) and move on through Word and Spirit to illumination and the process of sanctification until, at last, in heaven we see Christ face to face. (George and McGrath 2003, 4)

George attributes this perspective to the “deadly divorce between theology and spirituality” in evangelicalism. Most recent work on spiritual formation has been conducted by Protestants, especially evangelicals. It is beyond the scope of this dissertation to prove which order of the spiritual journey is correct, but my impression is that evangelicals need to review their model.

It is helpful to note here that the Orthodox Eastern tradition regards theosis or union with God as the goal of sanctification. Orthodox theologian Kenneth Paul Wesche quotes the patristic formula, adding his comments in parentheses: “God became human (without ceasing to be God) that humanity might become God (without ceasing to be human)” (1999, 30). Central to the doctrine of theosis, as postulated by Origen, is the premise that humanity was created in the image of God. Elaborating on the second half of the formula, Wesche states that, in human beings, there exists latently the image of God; therefore, humanity is still in communion with the divine nature. Orthodox Eastern theology has contributed much to my understanding of the Trinity and of perichosis, the eternal dance of human souls with God. In the Reformed tradition, restoration of the image of God by becoming like Christ is the central thesis of person-in-formation.

b. Persons-in-community formation to become a people of God

One of the purposes in Christian spiritual formation is to establish a people of God. The biblical records document God is continually gathering and forming his people. The building and rebuilding of the temple receives considerable attention in the Old Testament narratives, but there is a noticeable shift of emphasis from the temple as a holy place in the Old Testament to the temple as a holy people in the New Testament. Kang (2002) concurs with this observation, noting that the centre of biblical theology and spiritual formation is a people of God. He suggests that the people of God may be in communion with those of the past and with those in other lands. The people of God constitute a worldwide community called by God for his purpose as revealed by this covenant: “I will take you as my own people, and I will be your God” (Exod. 6:7). Basically, the foundational people of God are those who have responded to God in the Old and New Testament eras.

The people of God is one of the three major images Paul uses to describe the Church. The other two are the body of Christ and the temple of the Holy Spirit. Church or ekklēsia means “the called-out ones.” Ekklēsia, both in the singular and plural, may be used to define (1) a local community of those who profess faith and allegiance to Christ, (2) the universal Church, and (3) God’s congregation (Pate 1996, 95). The implication here seems to be that, while all the people of God comprise the universal Church, not all local congregations are made up of the people of God. Only God will know who his people are. The universal Church refers to the people of God whom God has elected to be his before creation. While it is likely that most of these elected persons are in the local denominational churches, it is also possible that many are also in Christian faith communities that are not part of these institutional churches.

The concept of the Church as the people of God reveals the special relationship of God with this group. Instead of adopting an existing nation as his people, God created a group of people for himself. This group includes not only Jews but also Gentiles. Thus, Paul is able to tell the Thessalonians that “we ought always to thank God for you, brothers loved by the Lord, because from the beginning God chose you to be saved through the sanctifying work of the Spirit and through belief in the truth. He called you to this through our gospel, that you might share in the glory of our Lord Jesus Christ” (2 Thess. 2:13–14).

Within the Church or the people of God, both individually and collectively, dwells the Holy Spirit. Paul writes to Christians in Corinth that they are God’s temple and that the Holy Spirit dwells in them (1 Cor. 3:16–17), later adding that their individual bodies are the temple of the Holy Spirit (1 Cor. 6:19). Theologian Richard E. Averbeck notes that “[a]s an individual ‘temple of the Holy Spirit,’ the Christian is part of the community ‘temple of God,’ the church” (2008, 43). He argues that a biblical theology for spiritual formation has its roots in the work of the Holy Spirit in Christians, the Church, and the Church’s mission.

Whether understood as the Church or the temple of the Holy Spirit, the Christian faith community is chosen by God to be his people. These communities consist of persons who need to be spiritually formed so that they will become the people of God more fully. Spiritual formation in the Christian faith community occurs at two interconnected levels. At one level, a person becomes part of a community of others who are individually “persons-in-formation.” Their interactions as they develop toward Christ-likeness are spiritually formative. The second level is the community itself. A community will develop its distinctive identity as it interacts with surrounding communities in their cultural and social diversity. The ultimate purpose of this persons-in-community formation is to establish a people of God in the world today.

c. Persons-in-mission formation in the kingdom of God and the healing of creation

This formative strand develops persons and their communities to become agents for God’s purposes of reconciliation for his kingdom. In a narrow sense, it is an individual’s actions of reconciliation. In a broader sense, it involves the reconciliation of a community of God’s people to God. In the broadest sense, it entails the reconciliation of the whole of creation. Christian spiritual formation may be visualised as a set of concentric circles: The individual is in the centre, the next ring is the community, and the outer ring is the world. The biblical concept of shalom encompasses a view of creation’s being in perfect harmony with God. Although this shalom has been achieved by Christ’s atonement on the cross, spiritual formation brings what Christ achieved into being in an individual, a community, and the created order. Paul writes to the Ephesians that certain actions “be put into effect when the times will have reached their fulfilment—to bring all things in heaven and on earth together under one head, even Christ” (Eph. 1:10). In his commentary on this verse, Calvin writes that “[t]he mode of expression is supposed to resemble one frequently used, when we speak of a whole building as repaired, many parts of which were ruinous or decayed, though some parts remained entire” (2003, 205). Reflecting on the same passage, F. F. Bruce notes that the reconciliation Paul meant “is the reconciliation of human beings to one another, as a stage in the unification of a divided universe” (1984, 261). In God’s timing, complete reconciliation will be achieved. Christian spiritual formation is the process God uses to bring his plans for the redemption of heaven and earth to completion.

When Jesus said to religious leaders, “I tell you that unless your righteousness surpasses that of the Pharisees and the teachers of the law, you will certainly not enter the kingdom of heaven” (Matt. 5:20), he was not talking about life in heaven but life on earth in the kingdom of God.[5] Willard (2010) similarly argues that the kingdom of God means “God in action” in the world today. This action includes spiritual formation as believers try to become like Christ. The key concept of the kingdom of God is expressed in Christ and his resurrection. Willard describes Paul as using “kingdom language” when he wrote Colossians 3:1–3, which are “pure spiritual formation verses” (2010, 41, 43; Author’s italics). Explaining to the Colossians that their spiritual lives begin on earth with Christ, Paul notes that “[s]ince, then, you have been raised with Christ, set your hearts on things above, where Christ is seated at the right hand of God. Set your minds on things above, not on earthly things. For you died, and your life is now hidden with Christ in God” (Col. 3:1–3). Willard remarks:

Spiritual formation and discipleship then become natural responses to the gift of life in the kingdom of God through faith in Jesus Christ. The kingdom of God becomes the texture and the energy of our spiritual formation in Christ. (2010, 56)

In summary, the goals of spiritual formation is (1) to develop persons to become like Christ, (2) to form a people of God, and (3) to enable persons and their communities to become agents of reconciliation for God’s kingdom. Spiritual theologian Evan B. Howard affirms the point as follows: “Conformity to Christ is achieved in approximation through authentic increase as individuals begin to act and to feel like Christ, as communities participate more and more in the charismatic life of Christ, and as the world is subject to a growing influence of Christ through the community of the king” (2008, 278). Christian spiritual formation is a process grounded in God’s covenant and divine-human interactions through the Holy Spirit.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Averbeck, Richard E. 2008. Spirit, community, and mission: A biblical theology for spiritual formation. Journal of Spiritual Formation and Soul Care 1, no. 1: 27–53.

Bock, Darrell L. 2008. New Testament community and spiritual formation. In Foundations of spiritual formation: A community approach to becoming like Christ, ed. P. Petit, 103–17. Grand Rapids,

MI: Kruger.

Bruce, F. F. 1984. The epistles to the Colossians, to Philemon, and to the Ephesians. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans.

Calvin, John. 1960. Institutes of the Christian religion. Trans. F. L. Battles. 2 vols. Philadelphia: Westminster Press.

______. 2003. Commentaries on the epistles of Paul to the Galatians and Ephesians. Trans. W. Pingle. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books.

Erickson, Millard J. 1999. Christian theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books.

George, Timothy, and A. McGrath, eds. 2003. For all the saints: Evangelical theology and Christian spirituality. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press.

Johnson, Suzanne. 1989. Christian spiritual formation in the church and classroom. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press.

Kang, Steve S. 2002. The church, spiritual formation, and the kingdom of God: A case for canonical-communion reading of the Bible. Ex Auditu 18, no. 1: 137–51.

Hoekema, Anthony A. 1989. Saved by grace. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans.

Howard, Evan. 2008. The Brazos introduction to Christian spirituality. Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press.

Latourette, K. S. 1975. Beginnings to 1500. Vol.1 of A history of Christianity. Peabody, MA: Prince Press.

Leith, John H. 1981. Introduction to the reformed tradition: A way of being the Christian community. Rev.ed. Atlanta, GA: John Knox Press.

Lightner, Robert P. 1994. Salvation and spiritual formation. In The Christian educator’s handbook on spiritual formation, ed. K. O. Gangel and James C. Wilhoit, 37–48. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker

Books.

Martin, R. P. 2002. Word biblical commentary: 2 Corinthians. Waco, TX: Word Books.

Moo, Douglas. 1996. The epistle to the Romans. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans.

Mullen, Bradford A. 1996. Sanctification. In Evangelical dictionary of biblical theology, ed. W. A. Elwell, 708–13. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books.

Pate, C. M. 1996. Church. In Evangelical dictionary of biblical theology, ed. W. A. Elwell, 95–98. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books.

Packer, J. I. 1985. Regeneration. In Evangelical dictionary of theology, ed. W. A. Elwell, 924–26. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books.

Vos, J. G. 2002. The Westminster larger catechism: A commentary. Ed. G. I. Williamson. Phillipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian and Reformed.

Wesche, Kenneth Paul. 1999. Eastern Orthodox spirituality: Union with God in theosis. Theology Today 56, no. 1: 29–43.

Willard, Dallas. 2002. Renovation of the heart: Putting on the character of Christ. Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress.

______. 2010. The gospel of the kingdom and spiritual formation. In The kingdom life: A practical theology of discipleship and spiritual formation, ed. Alan Andrews, 27–57. Colorado Springs, CO:

NavPress.

Endnotes

[1]. Obscurantism is defined by Reformed theologian John Leith as occurring “when the will of God is prematurely identified with some human pattern of conduct” (1981, 80).

[2]. By “created order,” I mean the culture, community, society, and world views surrounding the believer. Sanctification may be interconnected with an individual’s surrounding world and not be just a private activity.

[3]. Willard’s examination of the spiritual disciplines led him to a deeper understanding of human nature. The Spirit of the Disciplines: Understanding How God Changes Lives (1988) led him to look at character formation. See The Divine Conspiracy: Rediscovering Our Hidden Life in God (1998) and Hearing God: Developing a Conversational Relationship with God (1999). In Renovation of the Heart: Putting on the Character of Christ (2002), Willard formalised his thinking on spiritual formation. His next two books were an expansion on the same theme (Willard and Simpson, 2005; Willard, 2006). Willard has made many of his articles available online at http://www.dwillard.org/default.asp.

[4] This diagram is adapted from Angela Reed’s diagram, “Three Foundations of Spiritual Formation” (2010, 160). Building on theologian Jürgen Moltmann’s theology of hope and his understanding of the Trinity, Reed identifies person, community, and mission as the three foundations of spiritual formation. She uses these to develop her theology of spiritual guidance in her PhD dissertation. This diagram also appears in her book based on her dissertation (2011, 116).

[5]. Matthew 5:20 is to be understood in the context of Jesus’ teaching on the kingdom of God. Theologian Donald A. Hagner’s comment on this verse is that “[e]ntrance into the kingdom is God’s gift; but to belong to the kingdom means to follow Jesus’ teaching” (1993, 109).

Soli Deo Gloria

Share